Travis went to Europe and Alyssa went to Chattanooga. All to find out more about your favourite fossils. We bring you some news on extraordinary palaeo discoveries, a fascinating interview with Dr Indrani Mukherjee about the state of geoscience in Australia and her research into Earth’s earliest life, and Alyssa ranks 2025’s big hits (come at her).

__

Tess Gallagher, Dan Folkes, Michael Pittman, Tom G. Kaye, Glenn W. Storrs, Jason Schein; Fossilized melanosomes reveal colour patterning of a sauropod dinosaur. R Soc Open Sci. 1 December 2025; 12 (12): 251232. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.251232

Delclòs, X., Peñalver, E., Jaramillo, C. et al. Cretaceous amber of Ecuador unveils new insights into South America’s Gondwanan forests. Commun Earth Environ 6, 745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02625-2

Episode Transcript:

Travis (00:08)

Hi, I’m Travis Holland. This is Fossils and Fiction and my co-host is Alyssa Fjeld. Hi Alyssa, back for 2026!

Alyssa (00:17)

Back for more, right where we started. Travis is on a grand tour of Europe at the moment, is my understanding.

Travis (00:24)

A grand tour indeed. Yeah, no three countries. The Netherlands, which I leave today as we’re recording and then I’m off to…

Norway. That’s going to be a lot of fun. I hear I’m visiting your ancestors while I’m there. And then the UK. And in the UK, I’m going to catch up with some previous guests of the pod as well. May or may not record something for a future episode, but Tom Jurassic, who’s well known in the Jurassic Park fan community and also Saskia Elliott, who is a geologist down on the Jurassic coast.

Alyssa (00:37)

you

Travis (00:57)

I’m going to spend four days down there and hang out with Saskia. So I’m really looking forward to that part of the trip. I’ll go to every museum I spot while I’m here. So I took the train from Amsterdam down to Leiden and discovered the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, which I had not heard of before.

Absolutely fantastic museum actually. Their displays are really, really beautifully laid out. The building is extraordinary in and of itself. In terms of paleontology, it probably won’t surprise people to know that there’s not a whole lot of Mesozoic and earlier fossils found in the Netherlands, but

they do still have an active program and they send research teams out across the world and so they have this nearly complete magnificent T-Rex specimen called Trix which they uncovered in the US and then brought back here to the Netherlands.

Trix is worth the price of admission alone, but they also have a bunch of other dinosaurs and things as well. And I’ve put a video up on our YouTube, a little, a little tour of that and some photos as well up on Instagram. yeah, if people want to check out the Naturalis Biodiversity Center here in the Netherlands in Leiden, I highly recommend that as a visit if you’re in this part of the world.

Alyssa (02:19)

Yeah, that’s incredible. Travis sent me some of the photos of the museums he’s been visiting as he’s been gone. And if you’re familiar with the kind of dinosaur display that Melbourne Museum currently has for its triceratops, believe me, you’ll love this. It’s got the same iconic, like, dual-tone lighting and posing. It looks really fantastic. I mean, even just from the photos.

Travis (02:38)

Yeah,

yeah, the display of of Trix is really fantastic and you’re right, very similar lighting and setup. You come around a corner and there she is. yeah, quite, and as I say, the…

There was a lot of, stuffed animals, but I’ve not seen them displayed in quite this way before. You enter into an undersea environment first. And so it feels like you’re under the sea. And as you walk up the ramps and get higher and higher, the life at different, you know, literally at different levels,

rises. So all this life from all around the world as you walk from the bottom of the ocean up into sort of rainforest level and progress up in height you get there and so there’s a moment where it looks like you can see from under the water and you’re looking up and you can see the polar bears and things above you above the water line and then likewise you can see back down into the water from when you when you get up

that level. So yeah the displays are really really cool and the building as I say is absolutely fantastic as well so very cool place.

Alyssa (03:43)

feel like

you’re describing like an ideal museum for a night at the museum style situation. Like, I want this gallery to come to life harder than I’ve, I’ve wanted any other gallery to do that before. That sounds incredible. Could you imagine?

Travis (03:55)

You

It would be frightening. are a lot of animals there. Usually you see them in display cases. This setup was quite different. You walk through the pathway. was really cool.

Alyssa (04:00)

Hahaha!

I did not do a tremendous voyage like you are doing currently for the holidays, but I did go back to the US to visit my parents. So for those of you playing along at home, I am originally from the Southeastern US. I don’t sound like it because my mom would not have tolerated this, but that’s where I’m from. So I went back to Chattanooga over the holiday season.

and I got to see two of my nieces and one of them is I think about five now and she gave me a Christmas gift related to my job. So first she gave me this beautiful geode that she cracked open herself. How good is that?

Travis (04:53)

That’s beautiful. Yeah.

Alyssa (04:54)

I

asked her, you what rock is this? And she very like, unadult was just like, it’s quartz. It was like.

Travis (05:02)

very matter-of-fact. You don’t mess with geology.

Alyssa (05:03)

And she made,

no, like she’s ready for the career field that is correct. Her parents are both botanists, but no, no, no, like look at this beautiful card she made me for those of you at home. I’m holding up a lovely piece of art. It’s a picture of me.

Travis (05:10)

Mm-hmm.

Alyssa (05:21)

and I’m holding what she said was a fossil. It looks a little bit like a pickle, but I see it, I see it. And then she put in her favorite dinosaur skull, which she refused to explain what it was, and her favorite pterosaur skull, which was, I think she just said pterosaur, but she knew the difference, excellent.

Travis (05:41)

there is a paleontologist in the making right there.

Alyssa (05:45)

We gotta get them young. This is our agenda. in addition to that, I revisited some formative memories. I was looking back at my start into paleontology properly. for those of you who know a little bit about my history, I started my geology journey in undergraduate probably around 2012, 2013.

and I had like a whole narrative about why I got into it in my head that was so much more normal than I think what ended up actually happening. I had like blocked this out. I… When I first got to college, I was a big weeb because of course I was and I was like best friends with these two dudes who were really into tokusatsu which is

Travis (06:21)

I wait.

Alyssa (06:34)

It’s like what Power Rangers is, but in Japan it’s a whole genre of show.

So these two dudes that I really vibed with were really into this one tokusatsu show called Kamen Rider. And like, I remember getting really into Kamen Rider as well, but very specifically just like two of the shows, okay? Like I swear I can still function in society, but.

One of the ones, my favorite, and will always be my favorite because it was my first, was Kamen Rider Double, which is an incredible show about two 20-year-old detectives that merge into a single dude to fight crime and also their friend who is also a motorcycle is there. And you don’t need any other elements to make a great show, it turns out.

Travis (07:19)

Apparently not,

no.

Alyssa (07:20)

So in all of these shows, it’s like Power Rangers, there’s a bad guy that comes and they beat him up, right? And I had forgotten that in like the third episode of this show, the bad guy that they fight is an Anomalocaris.

Travis (07:34)

That is so random.

Alyssa (07:37)

And I must have seen this or like remembered it in enough proximity to starting to do paleo that I remember being like, that thing, that’s real, I know what that is. Man, paleontology is so cool. Look at how useful that was in my day-to-day life. I’m gonna study this. And it gets worse, it gets worse.

Travis (07:55)

What? Yeah. Makes sense.

Alyssa (08:00)

That Christmas I asked my parents, will you please get me this custom order Anomalacaris plush toy. I just, I think this animal, means something to me. It’s part of this journey. And it wasn’t enough to just have the stuffed animal. I can, so at this point I was dating one of those Kamen Rider nerds, God bless you Johnny. And at this point I said to him, you know what we should do is we should go get our portraits taken.

with this anomalocaris toy. And he was like, can I bring my hyper fixation too? And I was like, yeah, man, sure. And he’s like.

So we did. We went to the Olin Mills Photography Studio in Tullahoma and we paid 250 American dollars for photos that I had just blocked out.

Travis (08:52)

What is this? What? Okay. and second, every time we talk, you have some extraordinary deep Alyssa lore that just blows my mind.

Alyssa (09:09)

I’ve never used my free time for good. It’s only been to be a menace.

Travis (09:17)

Okay

well I’m going to put it here now that those photos will be available on our Instagram very shortly.

Alyssa (09:24)

Yes, and Johnny, I’m so sorry to not incriminate you I’ll cover your face with the face of one of the detectives from Kamen Rider Double I’ll pick your favorite one. I’ll pick Shodaro. I’m pretty sure it was Shodaro So you’d I’ll suffer, but you’ll be spared In other news the news

Travis (09:36)

Yeah.

That makes sense.

Yeah.

Alyssa (09:46)

News,

it’s time for paleo news, the news you can choose.

Travis (09:51)

we’re going to, we’re going to clip that. We’re going to clip that and use it in every episode.

So the paleo news, there was a paper published in December,

by Tess Gallagher and a team and it’s about fossilized melanosomes reveal coloring of a sauropod dinosaur for the first time. So scientists have found these melanosomes, the little cellular structures that produce pigment preserved in sauropod skin. We have these for a range of other dinosaur types, but my understanding is never for sauropods previously. So the fossils are juvenile diplodocus specimens.

in Montana or from Montana at the Mother’s Day Quarry. They’re about 145 million years old.

Tess Gallagher from the University of Bristol and her team found these distinct types of melanosomes preserved in the skin, which hints at the color. while they can’t pin down the exact color, the fact that there’s a variety of the melanosomes suggests that these weren’t uniform gray. You know, like we see in often popular depictions of sauropods is a kind of standard gray, particularly for Diplodocus. And there’s a particular movie, French.

that does this very well on the Apatosaurus, for example. But instead, actually juvenile diplodocus likely had speckled or patchy pigmentation, possibly for, you know, camouflage when they were small and vulnerable to predators.

The disc shaped melanosomes are particularly intriguing because they’re quite similar to modern bird feathers that create iridescence. So the team doesn’t say that the Diplodocus was shiny but what’s clear is that they have more complex coloration than we expected. So this has been published in Royal Society Open Science just in December at the end of 2025 and yeah it suggests that other sauropod

muscles might be hiding colour clues just beneath the surface if we only go back and look, which is pretty cool.

Alyssa (11:52)

Yeah.

It’s very rare in general that we get coloration preserved in the fossil record and with things like skin it can be especially complicated because color in the natural world comes from so many different sources. For example, sometimes coloration can be caused by grooves like microscopic grooves that catch light in a certain way and something like that is a lot easier to fossilize than the complexities behind pigment in say human skin. And I can understand making the diplodocus gray.

because we look at elephant and elephant big and elephant gray and whale also big also kind of gray you know so it makes sense but i i do love the idea that their babies are essentially bambi colored and i desperately need bambi diplodocus in my life like nothing it’s 2026 the world’s on fire let me have this

Travis (12:44)

Yeah, like a little orangey fawn coloured Diplodocus pop would be super cute.

Alyssa (12:51)

It would be so cute. I also have some paleo news. It’s not as cute, but it is really exciting for bug nerds like me. So I’m getting a lot of this information from the Natural History Museum’s write-up of it. I’m just gonna quote some sections because I think they do a better job explaining it,

in September of 2025, there was a write up about ancient insects that had been discovered in a quarry in Ecuador, the first time that Cretaceous era insects have been found in amber deposits in South America. And you might be thinking to yourself, no, I definitely remember there being some insects in amber found in that region. I promise you it’s a Berenstein-Behrs effect.

I thought I’d remember that too, but the more I read into it, the more I learned about kind of the fascinating history behind the way that amber preserves these fossils, which I think maybe the audience isn’t as familiar with, so I’ll briefly talk about that, and then we’ll talk about what was found in this quarry, because that’s also exciting. But essentially, in order to make amber, you have to have resin creating trees, trees that create sap.

the oldest amber dates to around 320 million years ago, but the first inclusions in amber of things that used to be alive, bioinclusions, only occurred in the Triassic period about 100 million years later. And for most of the time that we have amber up until about 125 million years ago, it doesn’t contain a lot of these inclusions and there just isn’t quite as much amber being produced.

we see a rise in the amount of amber in the fossil record between 125 to 72 million years ago in a period very straightforwardly called the cretaceous resonance interval or the Cree which is just delightful so that’s where i’m finding my joy

Travis (14:34)

You

Alyssa (14:36)

During this period, large deposits that are amber-bearing can be seen in what once was Laurasia. And the idea is that maybe conditions in the climate were a little bit different between Laurasia and Gondwana during this interval, and that’s why it’s less common to see amber deposits in Gondwana. So for example, Australia also has some amber-bearing deposits, but a lot of these are a little bit older, sorry, a little bit younger. So you have things like the amber deposits in

Tasmania or you have a couple of amber deposits found here in Victoria that friends of the show Lockie Sutherland and Maria gosh, she just got married and changed her last name, but she’s in my lab. Love you Maria They’re both looking at those sorts of projects those sorts of insects So when they say that it’s a rare find it’s a really rare find and especially in a humid jungle environment like South America I imagine that amber probably breaks down a little bit too quickly to be properly preserved

But really recently, a team led by a university professor from Madrid studied 60 samples of amber from the Genoviva quarry and found 21 different bioinclusions within them. So here we’re reading from the article, flies were the most common insects that were found, making up more than half of the bioinclusions. One of these is thought to be a new species of Mycophorites fly, an extinct group which is known exclusively from amber and found all over the world.

Among the finds were also a beetle, a springtail, a caddisfly,

in addition to finding all these whole animals, so there’s a hymenoptera, there’s a hymenoptera, you’ve got some flies, they also found a little piece of spider web and some parasites, as well as two parasitoid wasps, which lay their eggs in the bodies of other organisms, alien style, and a male midge. How cool is that?

Travis (16:24)

instead of a single find here, there’s dozens of things have been found in this amber, which is wild.

Alyssa (16:31)

Yeah, like the sheer amount of richness, like 21 different species sounds big and it is, and I think that’s a really exciting find. It’s a part of the world that we don’t have a lot of like this kind of evidence. And I think that this is going to help us create a more holistic picture of the ecosystem during this time period, know, stuff that was bugging the dinosaurs to quote a book that I have in eyeline.

yeah, how exciting new dinosaur skin and new things to eat the dinosaur skin

Travis (16:59)

Yeah,

I think where you’re thinking that there has been amber from that part of the world previously is because in one of the first scenes of Jurassic Park, that’s where they are. They’re mining amber.

Alyssa (17:12)

I knew it! I knew it was familiar!

I was today years old and when I learned that, so hopefully viewers now you know too. First ever South American amber deposits and maybe we’ll get our evil billionaires to make dinosaurs next. Let’s, know.

Travis (17:28)

Jurassic Park effect strikes again.

now for our special guest interview for the week, Dr Indrani Mukherjee is a geologist at the University of New South Wales. She focuses on the links between early life evolution, the origin of complex life and the formation of precious mineral deposits. So we cover all of that in

Indrani’s work, but we also get into the very interesting topic and I wanted to talk to Indrani because I heard her speaking on another show about what she sees as the crisis in geology education in Australia. And so we have a chat about that, what that actually means, what’s happening in geology departments across the country and the implications of that. So I hope you enjoy the interview.

Travis (18:26)

when we talk about the evolution of complex life, what’s the timeline we’re really dealing with? What counts as complex in deep time?

Indrani (18:34)

So we’re going back billions and billions of years ago and more specifically and this is based on the actual paleontological evidence that’s preserved in our rocks. We’re going back about 1.8 to 1.9 billion years ago. That’s when we start to see

You know, these are fossil evidence that are not disputed at all. absolute evidence of complex cells in the rock record goes as far back as 1.9 billion years old. And they’re quite global in occurrence as well. So you get those in Australia, in China, so similar age rocks in China, Russia, states, India, Australia. So, yeah.

this is the best evidence we’ve got of complex life. So the second question was, you know, what is complex life? it’s essentially what you and I are made of. We are made up of 34 to 37 trillion cells. And that cell is a very complex eukaryotic cell. I know it’s a big word, but it’s basically cells and within that cell.

You’ve got lots of different compartments for specific cellular functions. And so when life first started out, it was a very simple cell like that of a bacteria. But we do see evidence of the evolution of the first eukaryotic cell, or in other words, complex cell, about 1.9 to 1.8 billion years ago.

Travis (20:10)

What do we look for to actually figure out what a sort of biosignature in the rock is? What makes them tricky to identify in rocks that are that old?

Indrani (20:18)

Very, very good question and essentially a research topic very close to my heart. See, the thing is, when an organism is big enough and it has different components to it, hard parts, soft parts, soft parts might disintegrate and become part of the organic matter, but the hard parts get preserved. And, you know, that’s what we know as fossils. Biosignatures come in handy when

Your organisms are tiny and they don’t necessarily preserve well. But what does get preserved is their interaction with the chemical environment around them. So I am a geologist. I look at minerals all the time. Now, some of these minerals are formed because of no biological interaction whatsoever. They can form purely out of chemical reactions.

But sometimes those chemical reactions are mediated because and solely because of biology. So to give you an example, you can have magnetite, which is a very common mineral. But there’s bacteria that will precipitate magnetite crystals within the confines of the bacterial cell because it helps them with location, et cetera. So it actually has some sort of physiological

purpose that mineral within the bacterial cell. Then there are microorganisms that have metabolic waste and the reaction of that metabolic waste with the surrounding environment could also precipitate magnetite. And we know as a geologist, you can have magnetite in totally a biological settings as well. So we’re looking at the exact same mineral, but it is being formed one

due to biology, the other not. The challenge for us, particularly for geochemists such as myself, is to figure out when that’s biologically produced and when is it not. And so that’s the huge research topic that very closely I work on with chemists, et cetera, to figure out what’s biological and what’s not.

Travis (22:22)

Does that get much harder to figure those questions out when we look at somewhere like Mars compared to Earth?

Indrani (22:28)

Yeah.

So you will have seen the, you know, last year there was this fantastic news where they saw the presence of minerals like Vivianite and Grey Gideon and things like that. And everybody got super excited about that because on earth, that’s what happens when you involve biology. You suddenly see the precipitation of those minerals. Not to say that you can’t do it abiotically as well. So that’s, you know, that’s the conundrum. But

The better we understand Earth and the better we understand ancient Earth, particularly extreme environments, the better off we are. Chances that we will try and find evidence of life on other planets that are geologically similar to us, such as Mars. So yeah, I think we need a huge database on ancient Earth studies.

Travis (23:21)

Yeah, so figuring out those, you know, earth rocks could maybe help us find out if there’s life somewhere else as well.

Indrani (23:29)

We are assuming though that everything outside of Earth is potentially Earth-like. Should that not be the case, which is very plausible, then yeah, we’re a carbon-based life here. Everything that we are looking for outside of Earth may not be Earth-like at all. So there is that huge assumption there. But yes, the better we understand Earth.

the better our chances.

Travis (23:53)

And those are the kinds of questions that have animated your career. Tell me a bit about your career. How did you come into the field?

Indrani (24:00)

to be really honest with you, my first year in geology, it was too much. I think it was quite overwhelming. And, you know, we’re not taught geology in high schools. And so it was a bit of yeah, information overload and lots of new terms. And I didn’t like it at all. But it was really in second and third year, we had some amazing teachers back at the University of Delhi, where I received my geology education.

And the teachers were so good. this is where I really believe in the power of teaching. It can make a difference. It really enabled me to visualize the natural environment around us totally in a completely different way than I was doing before. And geology does that. The concept of time scales and understanding the different rocks and minerals and how did we get here.

Why does the landscape currently looks the way it does? it was, yeah, it was extremely fascinating from second and third year onwards. Coming to Australia was a huge step for me, but Australia, you know, it’s sad that things are changing now, but Australia’s reputation in geoscience is world class. We have some of the best geologists in this country and also geological locations. I mean,

the oldest evidence of life is, you know, is in the Pilbara, the stromatolites and lots of mineral resources, benefits of, you know, we all reap the benefits of that. A huge contributor to the GDP. So yeah, you have that amazing reputation, which kind of drew me. And I was going to work on a very different topic. I was at the center of excellence in old deposits.

very economic geology oriented, but at that time my supervisor was changing his research. And so I ended up working on this time span called the boring billion. At the time I was like, this does not sound right at all. This is not going to be a good PhD. Why am I working on this topic? But there was nothing boring at all as my PhD research suggested. And even

till date I’m continuing to work in that time span and going back to your first question, it is that time span when the first complex cell evolved and much of my research thus far is about, know, biologists will tell you how the first complex cell may have formed, but as a geologist I’m trying to explore why. When life can occur in simple forms, quite happily, why did we need

Why did we get to that complex cell in the first place? So yeah, that’s the, that was the crux of my research still is today.

Travis (26:36)

I’ve heard of this term the boring billion and I’ve often also heard people trying to challenge it just as you have to say actually it’s not not that boring at all so what’s the what is the boring billion and why should we cannot consider it so boring?

Indrani (26:52)

So the reason why, well, the main reason why some researchers consider it boring is because you don’t get those amazing sort of macroscopic or larger fossils that you see at the end of the boring billion. So you see these in the rock record at least, you start seeing animals, you start seeing bigger macroscopic forms, et cetera. So people think that that

the boring billion period, which starts about 1.8 to 0.8 billion years, that period is considered boring, is like, we don’t have larger fossils, et cetera, this and that. And so maybe evolution was delayed until they started appearing. So after about 800 million years, or 0.8 billion years. I think it’s the opposite. It’s like nothing happens when someone’s pregnant.

And then at the end of the nine months, you do have the baby. But those nine months are crucial for that macroscopic evolution to have occurred. So I think the boring billion period is actually that pregnancy period where much of the trophic levels and the microbial world had to be well and truly established to then sustain larger life forms. The evolution of the first complex cell

had to have happened before any life as we know it on our planet today. For any complexity, you needed to evolve that complex cell first and that happened. And subsequently, because that complex cell had better advantage over the simple life forms, you had to have established that competition between simpler and complex life forms, established the food chain and the microbial world, which is, by the way, the foundation.

of all life forms on our planet. And so until that was the, you know, that had to have been established before any fancy dinosaur or whatever else people get excited about, I’m very much fond of the micro world. Because I think we’re ignoring that even with the whole climate change discussion, we’re talking about how it’s going to impact humans, et cetera. Fewer studies, too few actually, have commented on the fact that the response of the microbial world to climate change

is going to be enormous and that’s going to have a huge ripple effect on the rest of the life forms on the planet. They are by far the most prevalent of all life forms as well. So I think the boring billion period, a lot happened in the micro world, which is not necessarily visible with the naked eye. people think, perhaps there’s not much going on. It is.

It’s all happening, but just at a very, you know, at a nanoscale or microscopic level, which we choose to sort of ignore. But there’s absolutely nothing boring about it. I mean, you and I are made up of the complex cell that evolved in the boring billion period. Surely it couldn’t have been boring.

Travis (29:36)

Yeah.

I love the analogy that you could consider it like a pregnancy, that it’s actually the development stage at which everything else was about to sort of become prominent, become a thing. So maybe we should be calling it the pregnant period or the pregnant pause or something like that instead.

Indrani (29:49)

you

I actually used

those exact words, the pregnant pause in one of my lectures at ANU this one time. So yeah, that’s a good one.

Travis (30:12)

why did the complex cell evolve during that period?

Indrani (30:15)

Yeah, so that’s basically what’s my PhD research on. And so I’ve come up with my own theory as to why it happened. Others have different ideas. So it’s really important to understand that the reason why it was termed as boring is because, you know, when people look at oxygen through time, so availability of oxygen in the atmosphere, in our oceans,

⁓ So oxygen availability through time, nutrient availability through time. They always noticed that during the boring billion, it was very low and stable. And so that was another reason why a lot of people thought, okay, that you don’t see much happening in the way of life, probably because, look, the oxygen concentrations were quite low and not much nutrients coming in either. So yeah, it was a very dull period in Earth’s history.

It was basically those conditions that led to the birth of the first complex cell. So biologists will tell you, and they’ve got their own arguments going on, two schools of thoughts where one believes or proposed that two simple cells came together in a symbiotic relationship where they both benefited from each other’s.

There’s the endosymbiosis theory of how the first complex cell formed. So endosymbiosis or symbiotic relationship. The other beliefs are proposed predation, where one larger simple cell engulfed another, also for the same purpose of benefiting from each other. So I was wondering, either way, predation or

Travis (31:48)

Hmm.

Indrani (31:59)

happy symbiotic relationship. What would trigger that? And I think what I came up with was the stress hypothesis in my research where I proposed that stress, environmental stress, in particular in the form of nutrient crisis was what triggered these interactions, whether it’s predation or endosymbiosis because

The fact is simple cell or prokaryotic life forms have, well, to date, are the, you know, the unseen majority, as they say, and they were the first life forms to evolve and they were very capable of living individually. Unless you, you know, that system was quite well developed before the boring billion period or the Archean in geological terms.

What happened in the boring billion period was a stark change in terms of nutrient supply to our oceans. And you can explain that geologically as to why that may have happened. It is a combination of tectonic motions and weathering and erosion on land, et cetera. Geologically, you can explain why you suddenly saw the oceans being very deprived of nutrients. But you want to thank

Travis (32:55)

Mmm.

Indrani (33:15)

⁓ your stars for that because it was that nutrient crisis that basically prompted single cell organisms to come up with a strategy to cope. it’s, know, it’s like during COVID, if you remember, a lot of businesses failed, but a lot of businesses came up with genius ideas to deal with the lockdown. And now they’re actually flourishing because they’ve worked out perhaps better ways of dealing with their business.

So it’s probably a similar thing that happened. It was the first striking variability in nutrient concentrations in our oceans that triggered the sort of interactions between simple cell organisms, which over time led to the origins of the first complex cell.

Travis (34:03)

What was the actual mechanism of the nutrient crisis that you think? What was missing? What got locked away or wasn’t available?

Indrani (34:12)

That’s a very good

question. Yeah, so it’s not just things were missing. The supply also changed in terms of what was being available. It wasn’t like nothing was being available, but the suite of bio-essential elements that were available prior to the boring billion was suddenly not available. You had a different suite of elements and the ones that were previously available were available and much lower.

So you had an overall decline in the amount of nutrient elements, but also the actual composition changed as well because we were weathering different kinds of rocks and they had different chemistry. So suddenly, yeah, it was that variability that basically sort of triggered these evolutionary milestones, if you have me say so, because

Suddenly the organisms were dealing with something totally different. And it’s already well known that if an organism is used to a certain element and if it’s absolutely essential, it will try and tap something else that’s similar in chemical properties. For example, if zinc is utilized and zinc is suddenly not available and cadmium is,

because of their similarities in chemical properties, the organisms will tap cadmium instead of zinc. And then cadmium may just either add or delete an extra function in the organism. all of this had to have been tried and tested by the organisms. The other thing that my biologist colleague always points out is it’s very hard to tap

elements from the aqueous system, so oceans. It’s a lot easier if someone else can bioaccumulate it within their cell. And so the concept of predation and endosymbiosis, it makes a lot of sense from the chemistry point of view because they’re like, ⁓ it’s more taxing to do it on your own. So you might as well, you know, if you’re running short on cash, you’ll probably want to go and spend some time with your folks just to save up a bit. It’s exactly that. And so

Travis (36:05)

Mmm.

Indrani (36:27)

These interactions that weren’t needed before because everyone was quite happy and content and flourishing with nutrients. Suddenly, when there’s scarcity, organisms are having to find out different ways to cope. And in the process, these interactions, obviously, over millions of years is when you start having, you you start seeing cells with compartments within, et cetera. So, yeah, that’s the geologist’s ⁓

a view of looking at it.

Travis (36:58)

What period followed the Boring Billion? Was it then the Ediacaran Or said a bit later?

Indrani (37:02)

Yes.

yeah. So, yes, we had the neoproterozoic and then the Ediacaran Yes. So we we see some soft. First of all, we see some really small animals. So animals, we all think of animals as these huge things and they are. But we had some really tiny ones to begin with. That was huge. So animals or metazoan evolution occurred.

shortly after the boring billion period. But to be really honest with you, Travis, we haven’t actually scanned through Earth’s history that well, we’re still discovering lots of new information. And I don’t know if you’ve heard of stromatolites, but they’re these layered sedimentary structures and they’re microbially driven. And the interaction between stromatolites and animals is quite interesting because

within these microbial mats you have a lot of oxygen production. So when oxygen concentrations are really low in our atmosphere, these microbial mats will have been, you know, really great sort of a refuge for these tiny animals at the time. And once oxygen concentrations were high enough to support larger life forms, that interaction kind of must have dissipated. But we do think that even though

Animal life evidence says that it’s 800 million years, so shortly after the boring billion period ended. But we think we could potentially push it back to about a thousand, which then falls within the boring billion. You might find evidence of ⁓ more complex sort of animals, because we had eukaryotes, that’s undeniable, but not the animal life, because everything we see on our planet today has to

Travis (38:40)

Mm-hmm.

Indrani (38:45)

is an ant, you know, apart from plants, it’s the metazoans. And so those tiny metazoans could be within those stromatolitic layers if we looked hard enough. But yes, work in progress. So animals shortly after boring billion and then soft bodied organisms that were suddenly leaving traces behind. So lots of trace fossils. And then

course you’ve got the explosion of live forms in the Cambrian onwards. So much focus has been on that those bigger sort of fossils, it’s easier to study, easier to find, but as we go further back in time the interest kind of declines.

Travis (39:11)

There is… ⁓

Those Ediacaran creatures are really bizarre, Like they’re almost alien creatures. They look nothing like anything else. It wasn’t until the Cambrian that you started to get sort of familiar life, as we see from this vantage point.

Indrani (39:40)

I think there’s a really cool video that I normally share with my students in first year, it’s Scripps Oceanography. Someone had this clever idea where they show the ocean and all the organisms in the ocean, but it all kind of comes down to the food chain and at the end of it is the microbe. And so the importance of how important

the microbial world is in terms of laying out the foundation for all life on the planet is really important. So that had to be there before any bigger life forms could, you you can’t move into a house if there’s no house. So it’s essentially just having that framework ready for more complex, larger organisms.

Travis (40:24)

Yeah, and that obviously had to have happened before the Ediacaran.

Indrani (40:28)

Yes, so

hence the the pregnancy. Yes.

Travis (40:32)

I heard you speak really passionately about the decline of geoscience capabilities in Australia.

that our reputation maybe is declining. What does this crisis actually look like? What’s actually happening here from your perspective?

Indrani (40:44)

The crisis looks like in the form of barely any geology department in the country anymore. we usually you’d have, know, every discipline has its own department. in Australia, least the geology departments have either been completely removed or they’ve been merged with.

other disciplines. And it’s obviously driven by student enrollments because the funding model at Australian universities is student driven. So a lot of income coming from students, particularly international students, et cetera. There is a lack of popularity. There is a lack of awareness. Not everybody knows about geology. Yes, dinosaurs, they have fun.

rocks and minerals and people forget about it. They don’t consider it as a career option. So there’s a awareness problem. There’s an image problem because when geology does get the attention of the media, it’s usually for the wrong reasons. you know, for example, mining disasters, environmental issues because of mining activities, acid mine drainage, et cetera. You will have heard of Rio Tinto’s

explosion of the really old indigenous heritage ⁓ site. So there’s an image problem, there’s an awareness problem, there’s an enrollment problem, and that all drives people making decisions at universities to think, well, this is perhaps not a viable course, or we don’t need that many academics to…

Travis (42:01)

Hmm.

Indrani (42:20)

teach this course, that’s not really going to be very popular with the younger generation, which is a real shame. don’t think we’re seeing… We’ve always had a very small pool of students wanting to do geology. I think if we can pitch our discipline better and knowing that the demand

with critical elements, et cetera, is just going to go through the roof. There are all these positions that are now available in the critical elements workforce, but we won’t have anybody to actually take those positions up because we’re not nearly training enough geoscientists. But once we realize that, I I really hope we realize now than later.

Travis (42:58)

you

Indrani (43:06)

But there will be a realization at some point that hang on, we don’t have enough geos. And suddenly there will be a huge demand. My worry is that we will have because the way the rate at which we are progressing in terms of culling geology, when we will need when there will be a demand and there will be a huge student increase, then we’re not going to have the necessary facilities or the environment to provide them the

the proper training. So that is a huge, huge concern. And the Australian Academy of Science released a report last year on what the critical scientific challenges are, where the gaps are, what will be needed in Australia in the next 10 years, you what kind of science capabilities and where are we lagging. And geoscience is one thing that was flagged as like absolutely

Travis (43:34)

Hmm.

Indrani (43:57)

critical in the next 10 years. in terms of the health of geoscience in Australia, it’s bad. And we can’t rely on overseas students. have to train. I’m a huge fan of wanting to train homegrown talent because with geology, things can get geopolitical.

And you want to ensure sovereign capability, which means that you are better off training your own geos rather than this import mentality of we don’t have here. No, they’re going to get the training and they’re going to want to go back and use that knowledge to help their country to explore for minerals, et cetera, et cetera. We need to ensure that we train homegrown talent here in Australia.

Travis (44:23)

Mm-hmm.

Indrani (44:43)

so they can contribute to Australian geoscience and the needs of the future here. Yeah.

Travis (44:50)

So, how do we do that then? What actually captures students’ imagination about geoscience? What’s the real hook that makes them realise the field matters?

Indrani (44:59)

I think we need to pitch how diverse the discipline is. A lot of the issues are because they think, I don’t want to go into mining, so I don’t want to take geology. But geology is not all about mining. I’m looking at evolution of complex life. We’re trying to define what biosignatures in rocks are. are paleoclimate studies. Should you be interested in climate change?

There are the discipline is incredibly diverse. You’ve got geophysics, you’ve got geochemistry, you’ve got geobiology, depending on which flavor of pure science you’re into, you should have a place in geology. There should be a place for everyone, essentially. So to pitch to our younger generation that it’s very diverse and to also pitch that it is

the need of the future. I think the younger generation are quite keen to make a difference, in particular towards climate, environment, et cetera. You can do that by being a geologist. You can’t save the planet if you don’t know about the planet. So if we pitch it in the sense that it’s very diverse and the fact that this knowledge is going to enable them to make a difference.

in the wider world in terms of protecting the environment or understanding past climate changes to predict future scenarios, you name it. There are lots of different ways of using the geological knowledge to whichever sort of career option you go into. And it would really help if we had geology or even just a little bit in high schools.

Because that way, when they take up the course, they know what they’re getting themselves into. This is not going to be like computer science or maths or whatever, where they have thousands of students. It appeals to a small percentage. But you want them, because they’re the ones who are going to actually make a difference. It’s a very nerdy subject. And you really have to be out there in the field.

Geology is a quiet taste and you have to spend a lot of time with the discipline to then make sense of things. It’s not an equation that you can balance out on either side. It’s the natural world. takes a long time to go out in the field, collect your rocks, look at them in detail. These days you’ve got AI capabilities that’s sort of revolutionizing.

there again, there’s another huge opportunity there for students who are more computer coding sort of driven because we have so much data and AI is changing the way we are evaluating data sets, et cetera. people don’t really understand how diverse and how interesting the subject is. we should, yeah, that’s, you know, you want to transfer all of that in the first year.

But the challenge is to get them

Travis (47:57)

So that’s for students then. Is there anything we need to do in communicating the importance of geoscience to the public? Is there something that could be changed in that communication?

Indrani (48:08)

We have, I think, outreach in geology is becoming more more prevalent. Back in the days, it was just left to a few people only. But I think now, you know, as when you go for your promotion, et cetera, you want to show that you have contributed to community, this and that. And so I think people are getting out of their comfort zone and

actually actively promoting their science because they’re getting something out of it too. And so it’s become part of the university system where you do evaluate your employees on the basis of how much outreach they’re doing, et cetera. So it’s becoming more common now. But I think with regards to geology, there’s so much of an image problem that I think all geologists should be

talking about the cool science that they do. Some of our science is extremely jargon driven. it’s, I as a geologist sometimes go, my gosh, what, I don’t understand. So it would be very hard for the public and we’re not very skilled in the way we communicate. think I once made a comment on Robin Williams science show that I think we need Taylor Swift’s marketing team to promote the discipline because

Travis (49:08)

You

Indrani (49:24)

The way we’re doing it is really bad and it’s super old school as well. So that’s lots of cool stuff happening in the geoscience world, but we’re too busy obsessing with rocks and not actually interacting with the public. And it is, you know, we need to get ourselves out there on the big stage along with the biologists and physicists and chemists. We’re being made fun of.

for too long on Big Bang Theory. I think that’s, I’m sorry, but that’s also a huge issue there. Yeah, think public, we definitely, we do, we’re doing a lot these days, but this is going to take time. It’s going to take time.

Travis (49:49)

You

Yeah.

So looking ahead then over the next decade, let’s get a little more positive. What really still excites you about geoscience? Where is your work going to take you and where’s the discipline going to go in 20 years? You know, what, what, are the big questions to address and deal with that that could be really interesting over the next 20 years?

Indrani (50:21)

Yes, so I’m really positive about the way we’re looking at deep time. So really old rocks to actually even define life. I think it’s a huge challenge these days. So I think the way forward would be to collaborate and make it interdisciplinary. All the big questions in science is you can’t, one discipline can’t single handedly.

Travis (50:25)

you

Indrani (50:45)

answer all the big questions. So if we are to look for signs of life outside our planet and in the next decade, I think there is a plan for Mars sample return, our ability to explore outside of Earth’s getting better and better. I think it’s going to be an exciting time to evaluate and understand extraterrestrial materials.

and to look for biosignatures. I’m quite excited to contribute as a geologist. So I work very closely with a chemist who’s also the director for astrobiology at UNSW here. And we’re looking, you know, he’s got the expertise to look at abiotic things and synthesize layers that may look like biology or not in the lab. Whereas I’ve got my geological expertise to look at

these absolutely fossiliferous-laid biological structures in deep time. So the confluence between chemistry and geology excites me a lot because when you’re looking at the natural environment, we are in our silos in our little departments, but in the natural world, everything is quite interconnected. So to be able to do that by having multidisciplinary

research, I think is the way forward. And we’re going to really, it’s an exciting time in that biosignature space. I also work closely with the minerals industry in terms of looking or helping them explore for zinc, copper and lead. And I think we also have a huge challenge ahead in terms of exploring for critical elements.

But then we need them, but that means that demand will drive a lot of mining. So if we can somehow process waste material to our advantage, that would be huge. So I’ve started working recently on assessing the critical elements potential of coal fly ash, which is a combustion product after you’ve burned coal.

Travis (52:33)

Hmm.

Indrani (52:47)

And we have heaps of it in New South Wales. They are considered as waste material, Australia’s second largest waste material, industrial waste. But if it’s got critical elements, then why dig up a whole mine when you can access it from a waste product? So I think that is also going to be huge in the next few years as to…

Yes, let’s find a deposit and mine, sure. But if we can extract those same elements from something that is considered waste, then you’re recycling that waste to your advantage. And it then gives the non-renewable sector an opportunity to directly contribute towards the renewables. So I think right now they’re all, you know, they’re at each other constantly. And we’re constantly debating,

Is this the way forward? But it doesn’t have to be that way. think the only way we can make this work is if they agree with each other and we move together ⁓ instead of in disparate groups. So that’s a big, exciting avenue, I think, in geology where we’re not looked upon as a problem anymore and we’re looked upon as a solution. But yeah, I think the government will need to fund lots of research on that front.

Travis (53:46)

Hmm.

Indrani (54:04)

to make it work. yes, so there geology will then collaborate with chemical engineers because they know the chemistry to extract. Whereas we can point out where the resources are, but ultimately you’ve got to extract it and process it. So processing is a huge, huge issue. We don’t get any of our stuff processed here in Australia. We’re sending it overseas for processing.

But if we can do it here, then that would be awesome.

Travis (54:35)

Indrani, thank you so much for your time. That’s been a wonderful chat and I’ve learned a lot. So hopefully we can get the word out about increasing the interest in geoscience and geology

Indrani (54:46)

Sounds good and thank you so much for having me.

Travis (54:58)

I really hope you enjoyed that interview with Indrani. It was certainly enlightening for me. We had such a great discussion and she has a lot of insight to offer, but also leadership for recovering the field of geology and its importance to Australia. Now, let’s have a look at some of the major discoveries in paleontology in 2025.

And what we’re going to do with these is I’ve got five discoveries for you, Alyssa, and then I want your definitive ranking order for these discoveries.

Alyssa (55:31)

Love an arbitrary list. Let’s go.

Travis (55:33)

I’m going to start with June’s discovery of the first ever sauropod gut contents. These were found in Judy, a diamantinasaurus from Australia. Her fossilized gut contents revealed conifers, seed ferns, and flowering plants that were barely chewed, which is direct proof for the first time that sauropods were indiscriminate bulk feeders or at least

the diamantinasauruses were and then probably also their close relatives. And then they let the gut microbiome do the work. first ever sauropod gut contents, that’s our first story for the year to rank. the second one I’m going to give you is nanotyrannus is real. We covered this at the end of the year. After 80 years of debate, two studies confirmed that nanotyrannus wasn’t just a teenage T-Rex.

Alyssa (56:03)

was

Travis (56:25)

It was in fact its own species living alongside the big guy. The dueling dinosaur specimen and analysis of other bones proved that it was a fully mature distinct Tyrannosaur rewriting decades of Tyrannosaur or T. rex specifically growth studies and revealing a much richer late Cretaceous predator community than we thought existed. Another T. rex story here, blood vessels were found inside the T. rex Scotty

in mid-year, Scotty, one of the largest T-Rex specimens ever found, yielded mineralized casts of blood vessels inside a healing rib fracture. Using synchrotron x-ray imaging, researchers created 3D models of the vascular network and it gives us a rear window into how dinosaurs, particularly T-Rex, healed from injuries. The next story for you to rank is…

Dinosaurs were thriving right up until the asteroid hit. has been some debate about this for quite some time. Fossils from the Nashitoibo member confirmed dinosaurs were thriving between 66.4 to 66 million years ago within 340,000 years of the impactor.

distinct dinosaur bio provinces with huge sauropods like Alamosaurus were flourishing across North America right up until the moment the lights went out with the Chicxulub impactor. So there was no gradual decline according to this paper, just sudden catastrophe. And again, this is something that’s been argued about for quite some time and this offers perhaps a defining shift in that particular debate and field of research. And then finally,

The last story to try and rank and give your definitive ranking Alyssa, just so everyone on the internet can come at you, Bolivia’s Dinosaur Superhighway. This is 16,000 theropod footprints plus 1,300 swim tracks the largest dinosaur tracksite ever found, all in one sediment layer, suggesting an ancient late Cretaceous coastal

Alyssa (58:17)

Ha

Travis (58:33)

thoroughfare stretching from Peru to Argentina. Trackways show walking, swimming, running and tail dragging behavior frozen in time. 16,000 theropods footprints and 1,300 swim tracks coming out of the dinosaur superhighway. So rank them.

Alyssa (58:55)

It’s hard Like like are we ranking them based on how like okay in my mind there’s three criteria There’s like the raw coolness of the thing like as you do like in paleo. That’s always a criteria, right? to how much

skill on the part of the people doing the research did it take because like it is always awesome when we find a cool fossil but it’s what that fossil tells us and how hard the researchers have like Worked to uncover that information that I think is like part of it So like I think that’s that’s that’s the last two kind of intertwining factors right is like how much work went into it versus like how much like a unique discovery is this and I

I wanna say based on those criterias, would put…

think I would put the… Like all of these are cool, be fair. But I think the blood vessels I would put last because I think as cool as it is that we’ve discovered we can apply this technology to these specimens. I don’t know if this is the case of like…

this is just a specimen we could do this kind of research on or if this is going to change the way that we think about using synchrotron x-ray imaging to get these kinds of impressions. If it’s the latter, I’ll bump it up in retrospect, but for now I’m going to put it there. And I’m going to do the same thing with Nanotyrannus because

Travis (1:00:11)

Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

Alyssa (1:00:20)

Look, okay, this is the same problem I have with Spinosaurus as somebody who is not a dinosaur person. I don’t know enough about what y’all are doing to make these determinations to have an informed opinion ever. feel, the science and the research changed so much and so much of it is like this ongoing massive argument and it’s like, okay.

If this is real, it will still be real in 10 years and I’ll rate it higher. But if in a year there’s some new study that says it’s a farce again, then I’ll have been justified putting it so low on my list. So we’ll see how predictive I am. I would then say I would put the…

I would put the dinosaurs were thriving right up until the asteroid hit because as cool as a discovery as this is, I think it’s one of those things where we’re gonna learn more about this deposit in the coming years. And while I think this is like an amazing thing to blow the doors open, I wonder like, like I want more. I feel like I’ve been given the first three chapters of a trilogy. Like I wanna know more.

And for that reason, I’m gonna put the first ever sauropod gut contents at number two, because I know the people that did this research a little bit, and it really does feel like what they did was sit with this discovery until they had learned everything they could feasibly learn.

in terms of the project they were conducting on the gut contents and they waited until they had like a really holistic understanding to come forward and I think I want more of that in the dinosaur paleo world. It’s like yes, yes, multiproxy approach. That’s what I want. Adele, I’m sorry. I’m sorry, Steve, poor Abat. And then…

Okay, I’m gonna put the Bolivian dinosaur superhighway at number one for two reasons. One, that’s an insane discovery. That’s so wild. It’s so cool. And it’s so improbable.

and I want this sort of thing to happen more for countries like Bolivia and Ecuador and you know all of these locations in the global south that have these historically understudied fossil records but that have so much evidence for things like Megaraptor evolution like there’s so much we don’t know about what dinosaurs were doing during this time period in this part of the world and yeah I think that’s insane it’s so cool that is the cool

is find of the year I’m so here for it okay what’s your ranking

Travis (1:03:00)

Great.

No, no, no, no, no, no, You’re the expert. You’re the expert. I’m just going to put your argument there and let people come at you about it.

Alyssa (1:03:10)

You’re gonna put, Alyssa

hates nano-tyranus on the caption of this episode.

Travis (1:03:14)

Yeah, that’s, that’s going

to be the title of the episode.

Alyssa (1:03:17)

Well let’s say they’re

a pod dinosaurs and things they all smelled really bad. They probably did, okay? They probably did.

Travis (1:03:22)

That’s probably true, yeah.

I don’t think theropods were necessarily the nicest smelling creatures around.

Alyssa (1:03:29)

Neither is the cougar, but look at the noble house cat. Good smelling animal.

Travis (1:03:34)

That’s it. We’re Fossils and Fiction for 2026. We’re back. It’s going to be a good year. Thanks for joining us. Make sure you check us out online on the various socials to see some things that we’ve been talking about. The show notes will have some more information as well. And of course, if you want to support the pod, the best way to do that is get yourself some merch. Alyssa’s proudly modeling our mug. ⁓ All of which features the artwork.

Alyssa (1:03:54)

We have a mug. It’s a very good mug.

Travis (1:04:01)

by Zev Landes our favorite paleo artist. Sorry to anyone else who’s been on the pod in recent years, but yeah, given, Zev put, put Zev put our work, our logos together, Scratch and Skitters, then he’s got a rank way up there for us too. So there you go. That’s my definitive ranking of paleo artists. Zev Landes, number one, get yourself some Zev Landes merch through our store.

Alyssa (1:04:05)

You

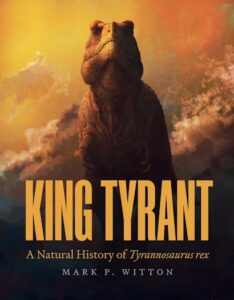

Sorry, Mark Whitten.

you

you

Definitely, it’s one of a kind. You won’t see it on his website. And he’s a fantastic small artist to support as you’re coming into the new year. We’re fantastic. Well, I’m okay And you should join us for all our new episodes in 2026. And if you wanna come on and chat with us, let us know. We are always curious to hear what you think about fossils and or fiction.